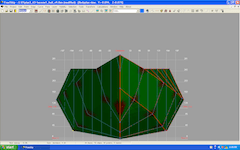

n the progress of learning to design my new kayak… you know its name already. I’m using Free!Ship, a CAD software running on Win XP virtual machine (with VirtualBox) on my Macbook. I haven’t used any CAD software before, haven’t designed anything 3D, not to say about a watercraft. So why designing a kayak!? Well, first, just for the fun of doing something yourself from A to Z. Second, though I’m no naval designer in any sense, I believe I have some guts on how a good kayak should be!

n the progress of learning to design my new kayak… you know its name already. I’m using Free!Ship, a CAD software running on Win XP virtual machine (with VirtualBox) on my Macbook. I haven’t used any CAD software before, haven’t designed anything 3D, not to say about a watercraft. So why designing a kayak!? Well, first, just for the fun of doing something yourself from A to Z. Second, though I’m no naval designer in any sense, I believe I have some guts on how a good kayak should be!

Many kayaks are designed for 70 ~ 90 kg paddlers on average, I’m not that bold, and I need something slimmer, lighter, with the drawback of sacrificing some load capacity of course. I’m re – modeling my kayak after Björn Thomasson’s Black Pearl, using just some publicly – available pictures of the boat. And it’s not a copy, there’re some modifications: slightly narrower beam, slightly less rocker, and slightly deeper V – bottom. And I would stick still to my familiar stitch & glue construction method.

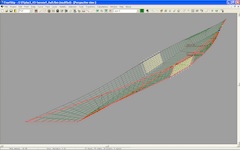

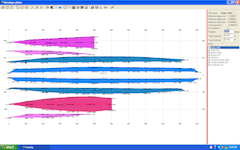

Why stitch & glue!? Strip build generally offers best boat shapes, but look at the Inuit people’s SOF (skin on frame) kayaks, those “hard chines” suit naturally to S&G, the method is simpler and takes less time (which I don’t really have much for now). It gonna be not an easy process: just for the hull, adjust the 60 control points back and forth, recalculate the stability and performance parameters, repeat again and again until you’re satisfied with the results. I hope I can finish the design in about a month or so.

Recently, I’d noticed that Japanese kayakers usually use kinds of slim, long kayak similar to the Black Pearl, that’s quite understandable cause the body – building of Japanese is Vietnamese alike, we’re not too bold. Use a slimmer, lighter boat, and pack your gears cleverly for longer trip!

It’s interesting to know that, in the old day, in building kayaks, the Inuit people has “recipes” to measure the size of the boat: length should be 3 times the height of the paddler, width should be the hip plus somewhere from 4 to 8 “finger”. Well, like shoes, boat is tailored to match the user.

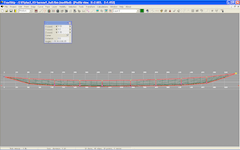

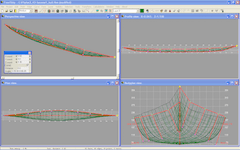

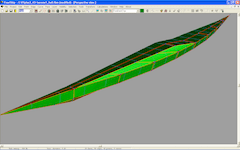

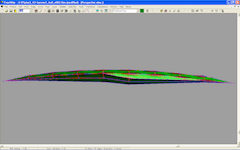

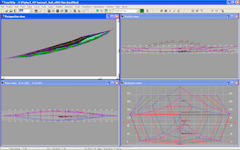

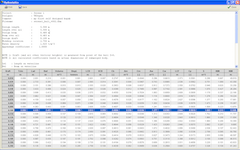

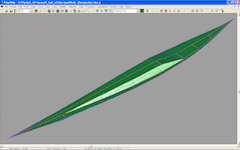

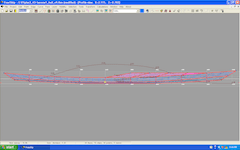

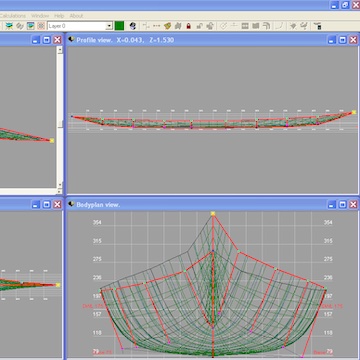

t tooks just a few hours to learn the new software and construct the basic 3D objects: hull & deck. The time – consuming tasks are adjusting the shapes and playing around with hydrostatics. Some basic measures: LOA / LWL (length overall / waterline): 5.50 / 4.44 m, BOA / BWL (beam overall / waterline): 0.483 /0.451 m, Draft: 0.1 m, S (wetted surface area): 1.66 m2, Cp (prismatic coefficient): 0.5619, LCB (longitudinal center of buoyancy): 0.5150, LCF (longitudinal center of floatation): 0.5192.

t tooks just a few hours to learn the new software and construct the basic 3D objects: hull & deck. The time – consuming tasks are adjusting the shapes and playing around with hydrostatics. Some basic measures: LOA / LWL (length overall / waterline): 5.50 / 4.44 m, BOA / BWL (beam overall / waterline): 0.483 /0.451 m, Draft: 0.1 m, S (wetted surface area): 1.66 m2, Cp (prismatic coefficient): 0.5619, LCB (longitudinal center of buoyancy): 0.5150, LCF (longitudinal center of floatation): 0.5192.

Additional hydrostatics parameters, VCB (vertical center of buoyancy): 0.059 m, Cb (block coefficient): 0.4684, Cm (midship coefficient): 0.8336, Cw (water plane coefficient): 0.6385, Displacement: 0.096 tonne… Well, I would not pretend I fully understand those parameters above, cause they contain insights into a boat that can only be correctly interpreted by an experienced designer. However, I’m tweaking around to optimize the parameters toward a higher Cp, higher LWL, and lower S.

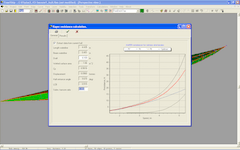

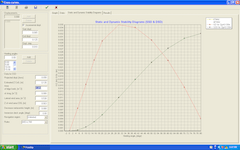

Drag (resistance) predicted by the KAPER algorithm looks fine till now, however, the displacement is sacrificed already, 96 kg, barely enough for me (65 kg) plus 30 kg of gears. This gonna be a demanding boat with low primary stability, not recommended for beginner. It takes some real world experiences to understand why low initial stability is indeed a good thing, and why a kayak which appears to be very stable on flat water could probably throw you up side down in bumpy conditions.

Some rough calculations on the energy required to propel a kayak. My target speed is 7 kmph, or 3.8 knots. From the numbers recorded by my Garmin over the years, in normal big rivers and sea conditions, speed is reduced by 1/3 compared to the ideal condition of flat water.

That is you have to struggle at 5 knots to assure that 3.8 knots. The Kaper algorithm tells you that, this Serene – 1 hull produces a resistance force of 27.35 Newton at 5 knots (or 2.57 meters per second). Making the multiply: 2.57 x 27.35, that’s the output required: 70.39 Watt!

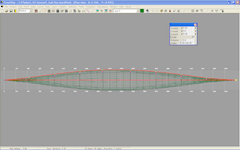

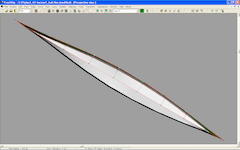

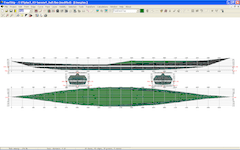

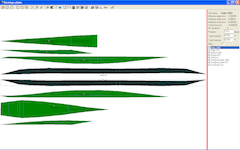

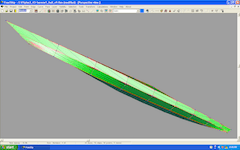

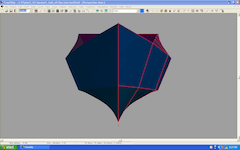

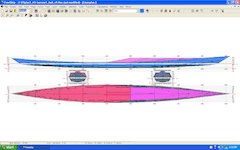

ade some good progress in the process of modeling my new kayak… For a human – powered watercraft, water doesn’t like complex curves and shapes I think, so they need to be as simple as possible (it is not too simple to come to that simplicity though). The model is then decomposed by Free!Ship into several “developable” plates, at this point, professional builders could just output the plates to a large CNC machine, which would precisely cut the plywood accordingly.

ade some good progress in the process of modeling my new kayak… For a human – powered watercraft, water doesn’t like complex curves and shapes I think, so they need to be as simple as possible (it is not too simple to come to that simplicity though). The model is then decomposed by Free!Ship into several “developable” plates, at this point, professional builders could just output the plates to a large CNC machine, which would precisely cut the plywood accordingly.

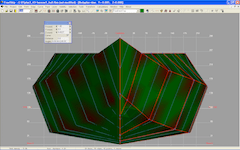

I print those plates to paper to make a 1:15 paper model. Cut the plates with a pair of scissors, then stitch them together using transparent duct tape. Making a paper scaled model would help verifying about the “develop – ability” of the product, double check if there is any design mistake, and give a clear view on how we should compose the pieces into the final boat. For simplicity, I didn’t draw details such as the cockpit, skeg, lines or hatches, just the basic shape of the kayak.

The paper model is a bit ugly (my hands are not too skillful though), but the pieces come together perfectly, the shape just looks like a bamboo leaf! This gonna be a long, thin kayak with very little freeboard! Next would be finding some free time to materialize all these drawing onto the plywood sheets. I don’t have a printer that’s large enough to print the plates in their real sizes, so I would just redraw them using offset table exported from the CAD software, actually, I prefer this manual method!

Back to the number 70.39 Watt, a heavy labour (such as a bricklayer) produces about 75 Watt on average, and for only 8 hours. You know what it’s like to paddle 10, 12 hours on a minimum basic, or even more, like I was paddling for 16 hours from Vũng Tàu back to Sài Gòn in my last trip!

The book Kayaks Of Greenland by Harvey Golden is a great guide for home builders, it contains dozens of kayak models ready to be built, with all the necessary drawings! I used some models from the book as references and comparisons when designing this Serene – 1 kayak!

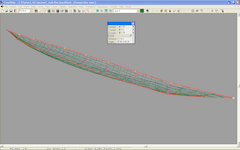

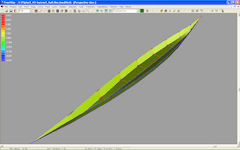

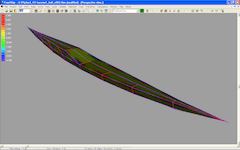

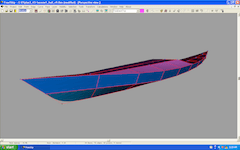

inalized my new kayak design, a considerable amount of work on optimizing the hull shape, adjusting it back and forth to find out the minimum drag numbers (based on the Kaper algorithm) while keeping stabilities and other parameters under control. Some numbers: LOA / LWL (length overall / waterline): 5.500 / 4.945 m, BOA / BWL (beam overall / waterline): 0.452 / 0.420 m. I reduced the boat width to exactly my hip plus 4 fingers (that is: 36 + 9 cm, my fingers are quite big, 9 cm for 4 fingers).

inalized my new kayak design, a considerable amount of work on optimizing the hull shape, adjusting it back and forth to find out the minimum drag numbers (based on the Kaper algorithm) while keeping stabilities and other parameters under control. Some numbers: LOA / LWL (length overall / waterline): 5.500 / 4.945 m, BOA / BWL (beam overall / waterline): 0.452 / 0.420 m. I reduced the boat width to exactly my hip plus 4 fingers (that is: 36 + 9 cm, my fingers are quite big, 9 cm for 4 fingers).

Designed draft: 0.11 m, Designed displacement: 95 kg, Cp (prismatic coefficient): 0.5475, Cb (block coefficient): 0.4064, LCB (longitudinal center of buoyancy): 0.5225, VCB (vertical center of buoyancy): 0.0690 m, LCF (longitudinal center of floatation): 0.5136, Cw (waterplane coefficient): 0.6445, S (wetted surface area): 1.699 m2, Aw (waterplane area): 1.329 m2, Am (midship section area): 0.034 m2, Cm (midship coefficient): 0.7466, KMt (vertical transverse metacenter): 0.196 m.

Predicted drags at 0.11 m draft (95 kg of displacement): 3 knot ~ 7.122 N, 4 knot ~ 12.622 N, 5 knot ~ 23.763 N. Predicted drags at 0.121 m draft (110 kg of displacement): 3 knot ~ 7.679 N, 4 knot ~ 13.611 N, 5 knot ~ 25.506 N. The hull is heavily optimized for speed in the [4 ~ 5] knot range with some sacrifices in stability and load capacity. Now that all “theoretical calculations” has completed, it would take a few months to build the physical boat to tell the real truths about the design! 😀

While 45 cm could be considered “extreme” for nowadays kayak (few available on the market has width at or below that value), it’s not really so with the traditional Greenland ones, some could be as narrow as 39 cm. Well for sure, it requires lots of skills to handle such a narrow boat.

The very important point here is the CG (Center of Gravity) used in calculating stability. The Sea Kayaker magazine uses a standard 25.4 cm as CG, as a reference point to compare different kayaks. I used the midpoint of VCB and KMt as CG, which is usually [12 ~ 15] cm for my cases.

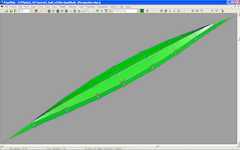

erene – 1 is quite a distinctive boat, originally took inspiration from the Black Pearl and the Anas Acuta kayaks, but in it current status, it shares not a single common point with them. The hull has been transformed into a light cruising one with long water line, deeper V bottom, little rockers and a very narrow beam (45 cm). There are times that I’m worrying on the feasibility of the design, except for some theoretical calculations, there’s nothing to ensure me that it would be a good watercraft.

erene – 1 is quite a distinctive boat, originally took inspiration from the Black Pearl and the Anas Acuta kayaks, but in it current status, it shares not a single common point with them. The hull has been transformed into a light cruising one with long water line, deeper V bottom, little rockers and a very narrow beam (45 cm). There are times that I’m worrying on the feasibility of the design, except for some theoretical calculations, there’s nothing to ensure me that it would be a good watercraft.

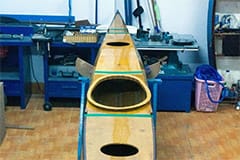

When you build something from a well – known designer, it’s already a well – proven boat. For Serene – 1, there’s no way to know, unless you build and trial it yourself. Eventually have some free time to proceed on today, first is cutting all the hull & deck framing stations in MDF. Can also see drawn is the cockpit template, this would be a very small one, 50×40 cm in dimensions, that’s what they called an “ocean cockpit”, you would need to climb over the aft deck and slide your legs into the hole.

The framing box showed up, by now, I could see how slim the boat would be, at this size, you just don’t ride the kayak, you essentially… wear it! Like an integral part of your body going to rough water, that’s how the feeling should be! Next would be the important task of drawing, and cutting the bilges from exported offset tables. For ones who don’t know, offset table is just a matrix of (x, y) coordinates, I use a very fine matrix (points every 5 cm interval) to precisely reconstruct the bilges on plywood.

One important note about various hull shapes (V – bottom, round, flat, etc…), cross section only affect stabilities, they have little effect on the boat’s speed which depends mostly on the waterline length and the wetted surface area. I tend to prefer hard chined V – bottom though.

About Prismatic Coefficient (Cp): a lower value indicates that the boat is more efficient at slower speed, a higher one tells that the boat is more efficient the faster it goes. So higher or lower Cp is neither good nor bad, it’s just that you need to know where is your desired range of velocity.

sing staples to clamp 2 sheets of plywood together, I then cut the hull’s planks, port and starboard, all is composed from 3 pieces. Then the deck’s pieces, and other parts: forward and aft bulkheads, skeg box and skeg blade… After 3 boats, I can now cut the wood with quite some accuracy. Sometimes, I’d wished to have the accuracy of a CNC machine, but such a machine that can cut in the 1.22 x 2.44 m dimension is not a possible option for most home builders, including me.

sing staples to clamp 2 sheets of plywood together, I then cut the hull’s planks, port and starboard, all is composed from 3 pieces. Then the deck’s pieces, and other parts: forward and aft bulkheads, skeg box and skeg blade… After 3 boats, I can now cut the wood with quite some accuracy. Sometimes, I’d wished to have the accuracy of a CNC machine, but such a machine that can cut in the 1.22 x 2.44 m dimension is not a possible option for most home builders, including me.

Next is the dusty job of beveling the edges of the plywood bilges, the edges are carefully bevelled at different angles along their lengths, to ensure a suitable gap, not too small, and not too big, for just a small amount of putty to go into the seams in a later phase. Then I joint the parts together using finger joints instead of the originally – planned puzzle joints. Straight finger joints, though not as strong as puzzle joints, they’re easier to cut and to fit, and most importantly, easier to align longitudinally.

This is very important, in my first boat, the 2 ends of port and starboard bilges differ as large as 5 ~ 6 mm. I can now confidently keep the tolerance under 1 mm along the 5.5 m length. Patterns of the joints are drawn on paper, photocopied into multiple sheets, glued onto the plywood and cut accordingly. I work carefully as to ensure a tight fit, an accuracy of a small fraction of a millimeter is required. This is quite hard when done by hand as my thinnest saw blade is already over 1 mm thick.

The phase measure twice, cut once

struck me once again 😢. As I’m about to joint the bottom bilges, I discovered that 2 pieces were incorrectly drawn and hence were cut 10 cm shorter compared to the design. Frustrated, I stopped working for a day, feeling really miserable…

I found out a way to cut (puzzle) joint nicely: just draw & cut something on the 1st piece of wood, the pattern doesn’t need to be too perfect, then use it as a template to draw and cut on the 2nd piece. This method is less error – prone compared to cutting twice following one same pattern.

he bigles jointed very well, with just some neglectable tiny defects, port and starboard pairs match perfectly. Before putting them all together to form the initial boat shape, I applied a layer of penetrating epoxy (epoxy thinned with xylene), taking care so that the amount of epoxy used won’t exceed 0.6 kg overall. For this job, I use a kind of elastic epoxy with the B5 slow hardener. There’re two kinds of epoxy: one hard and one elastic, with at least 3, 4 kinds of hardener available in the local market.

he bigles jointed very well, with just some neglectable tiny defects, port and starboard pairs match perfectly. Before putting them all together to form the initial boat shape, I applied a layer of penetrating epoxy (epoxy thinned with xylene), taking care so that the amount of epoxy used won’t exceed 0.6 kg overall. For this job, I use a kind of elastic epoxy with the B5 slow hardener. There’re two kinds of epoxy: one hard and one elastic, with at least 3, 4 kinds of hardener available in the local market.

I put a layer of fiberglass to the internal side of each joints before stitching the bilges. The deck is quite easy to form, since it’s very well geometrically – defined, I don’t even need to use steel wire and thus, avoid the unpleasant job of drilling holes, just duct tape over the edges, then dully apply the putty onto the bevelled seams. The hull is not that simple, with wires to fasten particularly at the two ends. Check the geometry of the overall shape, fasten the wires tight, then fill the seams with putty.

Cares are taken to use as little putty as possible, as I especially long for this to be a light boat. The same steps as in my previous boats, but done by more skillful hands 😀. Actually, I sometimes feel bored with those same things having been been done 4 times already, I should be planning for another boat in a different building method. But sure, not until I could feel I’m good enough at the current method, if you’re not “up to the level” yet, you would probably done wrong with whatever method used.

I wouldn’t advocate the use of thinned (penetrating) epoxy here, using it or not depends on the specific situations. In general, it should be avoided as it would add much more weight to the final product. However, the plywood available to me is not of marine – grade quality.

It’s made of a kind of “tea tree” wood, though apparently has some tensile strength, is quite porous and indeed lacks compressive strength. To compensate, some penetrating epoxy would help the plywood to become more firm and prevent delaminating in the long run.

poxy resin and putty are the most crucial parts in small watercraft building, yet they’re the most annoying, paranoidly sticky and easy to mess around. It takes me a long time to learn how to use them properly. After filling all the internal seams with the 511 putty (which I found very good for boat building), I put a layer of 5 cm – width fiberglass tape over them. I highly praise this double – weave glass tape: easy and quick to work with, precise laying, resulting in nice, tidy and tight bondings.

poxy resin and putty are the most crucial parts in small watercraft building, yet they’re the most annoying, paranoidly sticky and easy to mess around. It takes me a long time to learn how to use them properly. After filling all the internal seams with the 511 putty (which I found very good for boat building), I put a layer of 5 cm – width fiberglass tape over them. I highly praise this double – weave glass tape: easy and quick to work with, precise laying, resulting in nice, tidy and tight bondings.

With my previous boats, I haven’t got these fiberglass tapes yet, hence had to resort to bias – cut fiberglass, and it is next to impossible to make out a straight narrow strip of 5 cm, consider the mediocre local plain – weave 6 – oz fabric I was using. The very satirical thing is that this tout simple commodity of fiberglass tapes is not available anywhere in Vietnam market, and so I had to buy them on Amazon.com and have them shipped from the US, with delivery fee doubles the purchasing cost!

To further reduce weight, I only glass the internal side in part, the mid section slightly larger and around the cockpit, the place that could potentially expose to water. Next would go in the gunwales (a.k.a the sheer clamps) and the bulkheads. The gunwales are 15 x 30 mm long strips of wood, bevelled to match the deck’s profile. 7th image below: jointing 2 strips of 3 m wood to form the gunwale that covers the entire 5.5 m length. It’s so good a sensation to see the boat gradually take shape!

To completely clean epoxy, putty that stick to your hands, first scrub them hard with a rough piece of sponge, then rinse thoroughly with some acetone, finally wash with soap and water. I usually don’t wear gloves while working with epoxy, my hands just become clumsy with them.

A misc thought: stitch and glue is like a kid’s game, on a larger scale. Though it requires skills to build up a good functional boat, I don’t really see this as true “wood – working”, or any “piece of art” yet. That could be later, I don’t care, pour maintenant, tout ce que je veux c’est allez à la mer!

arious miscellaneous jobs in preparing for the next steps. First is glueing the skeg box and glassing the skeg blade (I use the “skeg in a well” as in my last boat, the skeg box is like a “well”, going through hull and through deck, a design that greatly facilitates maintenance and repair). Then forming the cockpit coaming by 2 nested narrow strips of 4 mm plywood, bending around the MDF frame cut earlier, the ply is so fragile that I had to brush it with a layer of epoxy to prevent cracks when bending.

arious miscellaneous jobs in preparing for the next steps. First is glueing the skeg box and glassing the skeg blade (I use the “skeg in a well” as in my last boat, the skeg box is like a “well”, going through hull and through deck, a design that greatly facilitates maintenance and repair). Then forming the cockpit coaming by 2 nested narrow strips of 4 mm plywood, bending around the MDF frame cut earlier, the ply is so fragile that I had to brush it with a layer of epoxy to prevent cracks when bending.

There’re still lots of things to be done before two halves of the peanut shell (a.k.a hull and deck) could be jointed together: fitting the starboard gunwale, fitting and glassing fore and aft bulkheads, install some cross – beam stringers, install the skeg box and it’s control line, making and installing the cockpit as well as the two hatches’ rims, build some lashing anchor points into the hull… any many other unnamed jobs. Forcing myself to slow down as not to let my impatience harm the kayak quality.

5th image below: the stringers glued and screwed in place, these stringers serve multiple purposes: help maintaining the boat width profile, support the skeg box and bulkheads, the stringer right behind the cockpit would help strengthen the deck (as the only way to get into the kayak is climbing upon its aft deck then slide your legs in). 6th image: the fore and aft bulkheads clamped in, ready to be sealed with putty and then glassed. Next would be the important job of installing the skeg box.

A large part on boat – building here (in Vietnam) is not about learning the techniques and executing them right. Mishaply, it’s about dealing with inferior – quality materials, working around with under – standard chemicals, paints, epoxy and various faulty wood – working tools.

A “secret” in this Serene – 1 kayak design: its lines are all mathematically very well – defined. I don’t know if this would add some gains into the boat’s performance, but in building, it’s easier to draw and cut, easier to stitch and form, less bending, less fastening, less clamping etc…

oat building is a labour – intensive process, and only skills and experiences could help to reduce workload and improve quality. Up until now, I’m quite pleased with the building, my 4th one. Today, I cut a slot into the aft hull to install the skeg box, the excellent Fein multimaster oscillating tool offers a nice cut as usual. Things went on smoothly, I have great confidence in this 5 cm fiberglass tape, it produces very fine and strong seam lines, so I decided to use just 2 layers (one inside, one outside).

oat building is a labour – intensive process, and only skills and experiences could help to reduce workload and improve quality. Up until now, I’m quite pleased with the building, my 4th one. Today, I cut a slot into the aft hull to install the skeg box, the excellent Fein multimaster oscillating tool offers a nice cut as usual. Things went on smoothly, I have great confidence in this 5 cm fiberglass tape, it produces very fine and strong seam lines, so I decided to use just 2 layers (one inside, one outside).

In my previous boat, I used 4 layers of fiberglass to secure the skeg box in place (which results into more weight added). The skeg blade is smaller, 30 x 14 cm, I guess a deeper V – bottom would track easier, so I would need a smaller blade just for some weather cocking conditions. Still stay indecisive about skeg’s control, I’m not totally happy with HW – 3‘s skeg control line, which runs over the aft deck, though perfectly functional, potentially could interfere with self – rescue actions.

Working on the skeg box vs. hull joint (the external side), then give the bottom a rough fairing to remove excess putty and smoothen out the edges, then apply 300 gram of thinned epoxy to it. A long busy day with lots of dust. Next would be exposing the hull to sunlight for 1, 2 days for the xylene solvent to completely vaporize, before glassing the external seams and other jobs. The hull part would receive an additonal overall layer of fiberglass once it’s jointed with the deck part.

Epoxy & putty are heavy, typical density is in [1.1 ~ 1.4] ton / m3 range. Wood & plywood are usually lighter, with the most normally used in [0.5 ~ 0.8] range. In order to use less epoxy, putty for joints, a good fit is required, hence wood working skills are anyhow important.

Use a small foam roller to stretch epoxy on fiberglass surface, and roll thoroughly, don’t use a brush, it brings in too much material. Don’t worry about the initial un – smooth result as epoxy has great “surface tension” and tends to make a much better gloss (as compared to paint).

ost major tasks on the hull has been completed, now continue on the deck part. First is cutting out the fore and aft hatches’ holes and fit some reinforcement rims (the plywood is weak, it can deform badly around the hatches in the long run). The Beckson hatches are quite small indeed, the largest are 8″ in internal diameter, have to live with that for now anyhow since Beckson does not have a larger size. I also made a rough fairing on the external side of the deck. Next comes the cockpit.

ost major tasks on the hull has been completed, now continue on the deck part. First is cutting out the fore and aft hatches’ holes and fit some reinforcement rims (the plywood is weak, it can deform badly around the hatches in the long run). The Beckson hatches are quite small indeed, the largest are 8″ in internal diameter, have to live with that for now anyhow since Beckson does not have a larger size. I also made a rough fairing on the external side of the deck. Next comes the cockpit.

The plywood is so fragile and easy to crack, so I turned to using wood for building the cockpit coaming. 2 thin strips of wood is combined to form the cockpit coaming riser. The strips are cut 3 mm thick and easy enough to bend without steaming, just use the C – clamps to force them following the cockpit template. The riser is quite high, 2 cm, and would be jointed with the plywood coaming lip 3 cm in width, all would be reinforced with some putty and fiberglass before jointing to the deck.

Using the angle grinder, I adjusted the bevel edges of the gunwales to better match the hull and deck. Also glassed the 3 hull’s external seams, each with about 80 gram of epoxy (240 gram in total). With experiences gained by now, I can control the amount of material used quite precisely. Hence, this gonna be the first boat which I could have weight truly under control, my projection is somewhere around 17 ~ 18 kg overall (everything not including the paddle). Let just see if I could make it there!

The Beckson hatches come with rubber o – rings that make the water – tight sealing. I made a mistake using some petroleum – based grease as lubricant on the rings, which could degrade and wear out the rubber. Have to clean it out and use some silicone – based grease instead.

One more ugly thing working with epoxy is that I usually need to mix them in a very small batches, just 30 ~ 40 gram or so (using an electronic scale). It seems counter intuitive, but the smaller the batch, the harder you would need to stir in order to have them mixed thoroughly.

onitnue working on the deck part and the cockpit. But first… some pictures to show off the boat shapes, still quite a long way to the final forms, but look fascinating enough to me already, to quote a popular architectural saying:

onitnue working on the deck part and the cockpit. But first… some pictures to show off the boat shapes, still quite a long way to the final forms, but look fascinating enough to me already, to quote a popular architectural saying: form, IT IS function

😀! 3rd image below: the cockpit coaming being reinforced with some putty in the corner, then a layer of fiberglass tape the under side. 5th image: cockpit being jointed to the deck. There’re some miscellaneous jobs to be done on the hull still.

15 anchor points to be built into the hull. First, I glued small wood blocks alongside the gunwales, then drilled two holes (1 inch apart) into each block. Plastic lines 5 mm in diameter (the one usually used in fishery net) are run through, then putty is filled in, this way, just a small amount of putty is used. When the epoxy has cured, pull the lines out, you would have some “tunnels” to run the lashing through. Finally, small pieces of glass would cover and strengthen the wood blocks.

The cockpit coaming is glued, then glassed with the deck, two layers of fiberglass (one under and one upper), it’s very strong now, can withstand the weight of my whole body (while climbing onto it). For such a narrow kayak and small cockpit (45 cm in width, less internally), I don’t install any foot brace or thigh brace, and even back rest, the cockpit almost fits my lower body. I have no idea for a seat for now, maybe that I would just sit on the bare bottom, or with a thin layer of mattress.

[13 ~ 18] kg is the usual weight range of wooden kayaks, with the lighter being used for tourings, and the heavier as “expedition boats”. Plastic or FRP (fiberglass – reinforced plastic) boats are much heavier, often in the [25 ~ 30] kg range. In order to go below 12 kg…

…you would need a SOF (Skin on Frame) design, or make use of the expensive carbon, kevlar fibers (usually found in racing boats). So wood is a very ideal choice for kayaks (as well as any small watercraft), and I would be very happy to have mine aimed at the 17 ~ 18 kg target.

arved and installed two wood blocks at the two ends to drill holes for the pulling knots (to further save weight, I won’t pour epoxy into the two tips, just the wood blocks with some sealing putty), sanding the cockpit coaming, glassing the lashing lines’ anchor points built into the hull, some more miscellaneous jobs before I can dry – fitting the hull and deck together. In the next couple of days, we’ll see the boat in its final shape! First two images below: inside and outside of the anchor points.

arved and installed two wood blocks at the two ends to drill holes for the pulling knots (to further save weight, I won’t pour epoxy into the two tips, just the wood blocks with some sealing putty), sanding the cockpit coaming, glassing the lashing lines’ anchor points built into the hull, some more miscellaneous jobs before I can dry – fitting the hull and deck together. In the next couple of days, we’ll see the boat in its final shape! First two images below: inside and outside of the anchor points.

Cut a slot in the aft deck for the skeg box to get through, then the hull and deck are ready to be jointed together, with just some epoxy (not putty) applied to the edges. The two ends, bow and stern, fit well, I just need duct tapes to press them together. The mid section requires some fastening as the plywood bent and and does not offer a perfect match. Nevertheless, the overall process is smoother compared to my previous boats, and I’m so happy to see the kayak taking on the designed shape!

I spent times going around and around the boat, watching the fruit of my efforts 😀! The hull shape looks very fine to me, the deck shape is quite crude indeed (not as cursive and fine as that of Hello World – 3, since the deck was drawn to be easy to build). But in essence, the lines, size, weight… all gives me a very comfortable and manageable feeling! Just a few more weeks from now and the kayak would be ready for her new life on water, can’t wait any more for that! 😀

With a flat deck, the kayak wouldn’t be particularly easy to roll, as once ‘turtled’, the deck becomes the bottom, and flat bottom is quite stable and difficult to turn over. So rolling is not a strong point of this design apparently, nor I did had rolling intention in mind!

Admittedly, I haven’t learned and practiced the Eskimo rolling techniques, and I couldn’t do it whatsoever, since my previous boats are too big and too heavy for me to roll. The techniques are in my (long – term) TODO list anyhow, at some points, I will try to master them!

ome tweaks here and there to smoothen the jointing edges between the hull and deck, putty – seal the bulkheads to the deck, then some slight overall fairing and sanding before putting on the final layer of fiberglass to the bottom part. The glass will marginally wrap over the deck (about 1 inch of overlapping) to strengthen and completely seal the joint. Deck would have no fiberglass on the external side, and would only be clear – coated with thinned epoxy and polyurethane (PU) paint.

ome tweaks here and there to smoothen the jointing edges between the hull and deck, putty – seal the bulkheads to the deck, then some slight overall fairing and sanding before putting on the final layer of fiberglass to the bottom part. The glass will marginally wrap over the deck (about 1 inch of overlapping) to strengthen and completely seal the joint. Deck would have no fiberglass on the external side, and would only be clear – coated with thinned epoxy and polyurethane (PU) paint.

4th image below: the deck thoroughly sanded with 100 grit paper, it looks quite fine now! In my previous boats, I was usually over sanding, with multiple grit – levels applied, and lots of efforts too. But now, I’d realized that I actually don’t need a furniture – grade finish (and I couldn’t do it as nice as a professional woodworker nevertheless). After all, a boat is a functional (not a show – case) object with lots of hard and harsh uses. A too perfect finish wouldn’t be of any practical good!

5th image: the deck has been stained with thinned epoxy mixed with color pigment (yellowish wooden color). The white duct tapes mark the area of wrapping when glassing the bottom. 6th, 7th images: glassing the hull exterior and wrap the fiberglass an inch over the deck. I used exactly 300 gram of epoxy mixed with dark brown wooden color pigment. A lesson learnt from the previous boat: use lighter colors for the wood to appear natural, too strong, deep colors look very… ‘artificial’.

About polyurethane (PU) paint: it’s a broad category of paint with different sub – types and applications, but in Vietnam, the term is narrowly and misleadingly meant to be one used for (semi – clear color) wood – surface finish only, as people is only familiar with that widespread use.

So if you want to see other types of the paint, say: Polyurethane, don’t say PU 😬! As the vendors will assume you know nothing about it, and by telling the chemical formula, you would be given more choices, don’t say PU, or you would be wrongly given the interior / inferior furniture finish!

pply a very thin epoxy fill – coat to completely cover the fiberglass fabric weaves, then peel off the duct tapes (together with the excess glass) with a sharp knife. The hull is then exposed to sunlight for the epoxy to completely cure, before given a very light sanding in prepare for painting. I paused for a few moments to watch her lines, well, with the singular exception of the “man – of – war”, all boats is always referred to as “she / her”, there must have been a reason for that, right!? 😀

pply a very thin epoxy fill – coat to completely cover the fiberglass fabric weaves, then peel off the duct tapes (together with the excess glass) with a sharp knife. The hull is then exposed to sunlight for the epoxy to completely cure, before given a very light sanding in prepare for painting. I paused for a few moments to watch her lines, well, with the singular exception of the “man – of – war”, all boats is always referred to as “she / her”, there must have been a reason for that, right!? 😀

Next come the job of installing some miscellaneous deck hardwares, the deck plate to seal off the skeg box, two small wood blocks acting like tiny cleats to hold the skeg control line… Some more unnamed works needed before the deck could be painted. You can also notice from the images that the deck has received another layer of thinned epoxy (mixed with color pigment). I was thinking over about the color scheme, but found out that it’s best to just have wooden colors on a boat.

7th, 8th images: using duct tapes to mask the areas out for painting. The cockpit would be painted first in dark brown color, like the hull, as well as some other parts on deck. After some simplest decorations go in, the deck and hull would be coated with transparent PU, just one layer on top and two at the bottom. After that is the final fitting (hatches, lashing lines, skeg control) and the boat would be ready for water, seems like I can’t wait anymore for it, to try out the boat this weekend! 😀

A bit off topic about the connotation of concepts… (in addition to polyurethane vs PU in the previous post) in Vietnamese the terms: áo ấm (warm jacket) and áo lạnh (cold jacket) vaguely refer to one same thing. In English, a wet suit and a dry suit are two different things! 😬

Reflected by the language, the Vietnamese are usually narrow – minded, they don’t take concepts into the very detailed, they don’t see things from different angles. They only see what’s immediately closed to them. As such, they’re easily tricked into seeing only what they / others want to see!

itting the Beckson hatches, fore and aft, is quite straight – forward and just takes about half an hour or so. The hatches are glued with silicone sealant, then screwed to the deck. I also applied a silicone – based mold – release spraying agent as lubricant, which secures a very fine and watertight fit. With these Becksons, I won’t have to worry about water leaking anymore, and even that the gears carried inside (e.g: electronics) don’t need to be packed in waterproof bags.

itting the Beckson hatches, fore and aft, is quite straight – forward and just takes about half an hour or so. The hatches are glued with silicone sealant, then screwed to the deck. I also applied a silicone – based mold – release spraying agent as lubricant, which secures a very fine and watertight fit. With these Becksons, I won’t have to worry about water leaking anymore, and even that the gears carried inside (e.g: electronics) don’t need to be packed in waterproof bags.

4th, 5th images below: the cockpit and some other parts on the deck painted. I decided to increase the amount of color pigment to turn the dark brown color into almost black to match that of the Beckson hatches. 6th image: I repaint the deck vs hull jointing line as the previous is quite ragged cause I used the wrong type of duct tape (which lets the paint leak underneath). In this Serene – 1, I don’t “cut corner” anymore, when something’s not right, I redo it until it’s good enough!

7th, 8th images: the hull painted, the dark brown color has become almost black now. I use a foam roller to quickly make the first layer of paint, then use a brush to apply the second (and last). It’s smooth enough, don’t have to sand & repaint another time as in my last boat. At this point, the boat is technically ready for water already, but yet some more painting and fitting jobs needed on the deck. Tell myself to be patient, I can’t even just wait for the paint to dry out in this moment! 😀

Well, some plastic parts on a wooden boat doesn’t look very attractive to some eyes, and initially, I’d preferred wooden hatches too, but such thing leaks no matter how good you make it. In my last trip to Đồng Hoà, I had to stop twice to drain water out when it has filled more than 1/3 of my boat.

So safety is the primary concern over aesthetics. One who’s paddled in rough conditions would understand the very fearsome instability of a boat half – filled with water, not only it’s more heavy to paddle, the whole thing becomes a very thrilling acrobatic game indeed.

ome final jobs required still to complete the boat: slight sanding here and there on the deck, some minimum decorations, all in white vinyl decals, then the final coat of transparent PU paint on deck. For decorations, there’ll be certainly the inevitable part, the Vietnamese boat eyes, the boat name and some texts stating the owner’s contact information. I’ll keep these to the fewest possible, standing from a functional point of view, and avoid any elaborate decorations, at least for now.

ome final jobs required still to complete the boat: slight sanding here and there on the deck, some minimum decorations, all in white vinyl decals, then the final coat of transparent PU paint on deck. For decorations, there’ll be certainly the inevitable part, the Vietnamese boat eyes, the boat name and some texts stating the owner’s contact information. I’ll keep these to the fewest possible, standing from a functional point of view, and avoid any elaborate decorations, at least for now.

3rd, 4th images: the decals in places, the boat’s eyes, name and contact information. This kayak has bigger eyes compared to those of my previous boats, as for it to see and travel wider, further 😀! Btw, Vietnamese is not the only people traditionally to have eyes on boats, but while others infrequently have eyes as decorative items, 99% of Vietnamese boats has eyes as an indispensable part, a kind of ancient belief that boats are living creatures, who have eyes and souls.

It took several more hours to install all the bungee lines, boat pulling knots at two ends (I just used a variation of the hangman knot) and skeg control. 5rd image below: the skeg control line offset – ed to starboard side, right after the cockpit, hold down by a cleat, for easier handling, and also for not interfering with the rear hatch. 6th image: the skeg blade in its maximum extending position. Now just wait for the paint to completely cure, and for the favorable tide to christen and launch the boat! 😀

The very small fraction of Vietnamese boats which doesn’t have eyes are of foreign immigrants (e.g: Chinese, Khmer…) who had settled in Vietnam long ago. Eyes have different patterns, by looking at their shapes, I can tell from which province of Vietnam does the boat come from.

Serene – 1 building takes less than 2 months to complete, not everything is as perfect as I was expecting, but the boat overall quality is much more satisfying compared to my previous boats. Not going to water yet, but its firm and compact body gives me a very pleasant feeling.

he final boat weighs at 21 kg (7th image), a bit heavier than my expectation (I was adding more materials in the later phases of building when thought that it’s already light enough, and the two plastic Beckson hatches add an additional 1 kg 😢). But anyhow, that’s fine still, I can comfortably transport it on my shoulders for considerable distance at that mass. Looking top down, the boat is slim and slender exactly like a bamboo leaf! Last image: me porting the kayak to water… 😀

he final boat weighs at 21 kg (7th image), a bit heavier than my expectation (I was adding more materials in the later phases of building when thought that it’s already light enough, and the two plastic Beckson hatches add an additional 1 kg 😢). But anyhow, that’s fine still, I can comfortably transport it on my shoulders for considerable distance at that mass. Looking top down, the boat is slim and slender exactly like a bamboo leaf! Last image: me porting the kayak to water… 😀

I took the boat to my routine 20 km paddling route today, having just one word to say: EXCELLENT! 😀 It rains heavily 2/3 of the route, quite strong wind at times, but small waves, relatively calm water. The first thing to recognize is the (predicted) low initial stability, took some times to get familiar with that. A novice paddler could be probably frightened in my boat though. The boat does not track as straight as Hello World – 3, and I need to deploy the skeg 1/4 down for most of the time.

Velocity sees a very good improve, I finished the route in 2 hour 50 minutes, compared to the 3 hour 30 minutes best time of Hello World – 3 on that same route, with quite a weak tide today. However, this is only initial measures, I need to thoroughly trial the kayak in many other routes and conditions to have some precise comments, e.g: with this narrow beam of 45 cm, I would certainly need a shorter paddle. Would post some paddling pictures and videos once I’m done with the testings.

With this narrow boat, the steadiness of your own body in motion is important. Hence, it does require some practices to completely handle the boat. For the moment, it’s too early to say about the kayak stability, especially that I haven’t had the chances to test it in rougher conditions.

However, my observations during the strong wind & some waves, the boat handles nicely. I feel it’s more stable in waves than on flat water 😀. When rain’s flooded about 6, 7 cm, it becomes even more stable, cause the kayak is approaching its nominal (designed) capacity.

ade several more ‘sorties’ with Serene – 1 the last week, and her name is Serene, isn’t it!? 😀 I’m now quite comfortable with her motion, especially her primary stability. The secondary stability comes to assure the initial lesser – secured feeling, though the marginal limit of which is still the subject of more testing. Windage is barely noticeable in most cases. It takes some practices for cockpit entry and exit, the small size would only have benefits once going to the rougher sea.

ade several more ‘sorties’ with Serene – 1 the last week, and her name is Serene, isn’t it!? 😀 I’m now quite comfortable with her motion, especially her primary stability. The secondary stability comes to assure the initial lesser – secured feeling, though the marginal limit of which is still the subject of more testing. Windage is barely noticeable in most cases. It takes some practices for cockpit entry and exit, the small size would only have benefits once going to the rougher sea.

Speed measured in several hours of paddling averages out in the [7 ~ 7.5] kmph range, that’s good! But please note that the conditions are mostly flat water with some winds, and it’s not a measure for whole – day paddling in true sea environment yet. In fact, I would be very happy to have my whole day sustained speed around 6 kmph, cause it’s very hard to keep up the same constant horse – power output at the end of 12 hours or more paddling session. Still lots of spaces for improving.

I’m not done with my testings yet. It takes time to adapt my paddling habits to the new boat, and to find out the best way to propel her. For example, the very narrow beam, in addition to the low seat, require much a shorter paddle. My standard 2.22 m paddle suddenly becomes too long, it sweeps far apart from the kayak body, and hence has some negative impacts on directional stability. I’m planning to build some Greenland – style paddles in the upcoming phases of the project.

As noticed in previous post, the kayak becomes more stable when has some water in her hold, as she becomes heavier toward the designed displacement at 95 kg. It doesn’t mean however, that water should be used as ballast for such small watercrafts (bottled water is fine I think).

I would spend the next month trialling the boat in various other conditions, e.g: carrying different amounts of load, heavy load in rough water… to find out if she is really suitable for the course of “about – a – week – long” trips. Day after day, step by step nearer to being far away! 😀

he more I paddle, the more I’m familiar with my new kayak, and the more I feel pleased with her. Maybe on my next boat, I should have the following motto boldly engraved on:

he more I paddle, the more I’m familiar with my new kayak, and the more I feel pleased with her. Maybe on my next boat, I should have the following motto boldly engraved on: built like a gun, run like a bullet!

! 😀 Been quite occupied with my works recently, so for now, I won’t put an emphasis on carrying out the next phases of the project yet, just casual paddling here and there a couples of weeks, to get to know more about the boat, and to enjoy the rainy season at its climax.

One minor problem with kayak at this beam, I realized, is that just a small shift in weight could make a directional deviation, it is not a problem with the boat’s structure itself, but with the motion of your body in action. Especially on long paddling, my lower body part becomes stressful and tired long before the upper part, so the need for frequent changes in sitting positions, and hence the effects on directional stability. I guess my lower body part needs some further exercising too.

I like making some short sprints with the boat, it takes up momentum easily, just after a few strokes, and makes it very straight on effort, or to see her gently riding down the waves, just like an Andalusian in dressage equestrianship! 😀 Well, when I really have some free time, I think I should build a standard K1 hull, to experience that extreme Olympic racing form, and to better understand the correlations between lines, speed and stabilities, and also for some practicing on flat water.

In my opinion, a problem with most commercially – available kayaks is that, the cockpits are usually placed too far aft. It’s easy to understand the reason, cause weights of paddlers are variable, they are not fixed. It’s better for the producers to make some ‘reservations’…

to place the cockpit a bit further aft, so that the boat could be trimmed rearward for heavier paddlers. And trimming rearward is wiser for most kayaks, which usually have a Swede form. For a self – designed boat like Serene – 1, it can be tailored to suit your very own measures 😀.

t’s good to see every parts of the boat work as intended. The hatches are completely watertight. When I left the hull out under afternoon sunlight for an hour for it to dry, the air inside warms up and expands, when I open the hatches, I can hear the sound of escaping air. That confirms not only the hatches, but the whole hull is airtight, and so they are obviously watertight. Then carrying gears inside could be housed with minimum protection against water (e.g: some normal plastic bags).

t’s good to see every parts of the boat work as intended. The hatches are completely watertight. When I left the hull out under afternoon sunlight for an hour for it to dry, the air inside warms up and expands, when I open the hatches, I can hear the sound of escaping air. That confirms not only the hatches, but the whole hull is airtight, and so they are obviously watertight. Then carrying gears inside could be housed with minimum protection against water (e.g: some normal plastic bags).

For the last two weeks, I only tested the boat on flat water, small river branches which are calm most of the time. Next would be some longer and rougher paddling. Been too busy lately and couldn’t keep up the planned pace of at least 40 km per week, and so my endurance has been falling drastically 😢! Also, I’m quite lazy at video shooting and editing, after all, you can’t make it as good as a professional cameraman, and upto one point, you don’t see a necessity for much showing off any more.

Sometimes, I wish I could just put everything aside, pick up the paddle and go, go light and go now! Nothing comparable to the paddling experiences, you and only you in the wild, and you don’t have to depend much on those delicate electronics to have a joyful journey, they’re just some more burdens. So maybe I my next trip, I would just leave the GoPro at home, a single small still – camera is stilled needed though. 4th image below: can only be happy when in open air and on bobbing water! 😀

With that “go light” determination in mind, all next fittings, equipments for the kayak would be kept to the minimum and simplest possible. The boat is now lightweight enough, I don’t need to carry the kayak cart along my trips anymore. If required, I would just port the boat on my back.

There’ll be no seat, just a small block of foam used as the back rest. Also no signal pole, just some head – mounted lights I guess. No marine compass fit on deck as originally planned, I would just use the Garmin instead (plus a tiny hand – held magnetic compass as backup).

ne of the things I’ve been concerning about since start designing the kayak is the spray skirt. The skirt follows a cockpit that has an unconventional size and shape, and after quite some searching on the internet, I couldn’t find a vendor who could supply an already – made spray skirt that fits my size. I could, of course, have one built on custom order, that is I would need to give them the exact drawing of the cockpit, that would involve many steps back and forth, and an expensive process too.

ne of the things I’ve been concerning about since start designing the kayak is the spray skirt. The skirt follows a cockpit that has an unconventional size and shape, and after quite some searching on the internet, I couldn’t find a vendor who could supply an already – made spray skirt that fits my size. I could, of course, have one built on custom order, that is I would need to give them the exact drawing of the cockpit, that would involve many steps back and forth, and an expensive process too.

I decided to make one my own, everything needed is already available in my workshop: some nylon fabric (the one used for thick raincoat), bungee cords, needle and thread… My sewing skill has always been terribly miserable, but the first step is done, with acceptable quality. Not a “spray skirt” yet, rather a “spray deck” covering the cockpit. Next would be sewing in the tube that goes around your waist which could be fastened with velcro tapes. Jack – of – all – trades is the sailor, isn’t he!? 😀

7th, 8th images: the tube stitched, an elliptical tunnel that goes around my waist, 36 x 28 cm in dimensions. By now, the spray skirt is almost completed, it fits the boat and my body very well, just gonna add 2 pockets on the two sides. If look into details, one would see the very rough, clumsy seam lines, cause I’m not really familiar with those needle and thread jobs (I broke 3 needles while sewing!). Anyhow, I’d got it done, and it should fullfill the important functionalities of a spray skirt! 😀

One of the advantages of D.I.Y is that things could be made to suit your very own needs, e.g: my spray skirt would have a belt fastened with velcro tapes, matching my waist closely, and two small pockets on the sides to hold miscellaneous things very much needed once under way.

Made of nylon fabric, the skirt is not as good as professional neoprene – built one, however, that would be suffice to do the job of keeping the water out, in rain or in heavy sea, but surely wouldn’t be suitable for rolling actions. Btw, I can’t find retail – selling neoprene here in Saigon anyhow.

he spray skirt works very well as anticipated: tight fit with the boat and my body, easy to snap onto the cockpit coaming, flexible enough for some torso rotation and other paddling movements. The velcro stickers seal the water well, and two pockets could hold the camera, and some other miscellaneous things. At least, it’s much better than my previously – bought skirt, which is of quite an amateurish design. Next is the important job of building a wooden Greenland paddle.

he spray skirt works very well as anticipated: tight fit with the boat and my body, easy to snap onto the cockpit coaming, flexible enough for some torso rotation and other paddling movements. The velcro stickers seal the water well, and two pockets could hold the camera, and some other miscellaneous things. At least, it’s much better than my previously – bought skirt, which is of quite an amateurish design. Next is the important job of building a wooden Greenland paddle.

The rationale of a Greenland paddle, as I understand, is that: the smaller blades put less strain onto your arms (while propelling the boat at a slightly slower speed compared to the larger wing paddle), and at the end of a long paddling day, you would end up covering almost the same distance, with less fatigue sustained, and this is specially true for lighter boats like Serene – 1. At least that’s my theory, and let see how this would turn out in practice. Well, to really know, you need to build one and test.

I start by jointing thin (1.5 cm) strips of wood to form the paddle, which would have the length of 210 cm, 75 cm for each blade and 60 cm for the loom. I choose to joint wood instead of starting from a single big piece, (it depends on the specific situation), but sometimes, glued wood is stronger, consider the strength of epoxy. The blade would be 8.5 cm wide, and the loom would be slightly oval in cross section: 3.3 x 2.8 cm. Next comes the job of meticulously carving down to the final desired shape.

The Bosch machine planer is very useful, most jobs could be done handily with it, I only need to use the hand planer on the edges. Much wood is removed, the paddle is quite light now. For a paddle, weight and balance is important, I check the object balance from time to time while working.

The plastic – blades, aluminum shaft paddle I’ve been using for a long time is kind of… a toy paddle 😀, it’s very fragile, I’ve always been worrying about breaking it in some power actions. But it is super super light. Need to finish and see how this Greenland paddle would prove himself in practice!

irst two images below: the paddle takes its final shape, it is quite light indeed. Next I would glass the two blades’ tips to strengthen them a bit to avoid cracks in collisions, then some little thinned epoxy, then paint the whole thing with the same kind of PU used for the boat.

irst two images below: the paddle takes its final shape, it is quite light indeed. Next I would glass the two blades’ tips to strengthen them a bit to avoid cracks in collisions, then some little thinned epoxy, then paint the whole thing with the same kind of PU used for the boat. Less is more

is the “principle of operation” of a Greenland paddle (compared to a wing paddle), but it would take times to really accomplish that. A completely different toy, and quite a separate way of using!

The next couple of weeks, I would just re – train myself with the new paddle. It’s quite a different style, the thinner blades allow movements very closed to the boat’s body, they enters water in almost a vertical manner. It takes time to suppress old habits, find out the most efficient way and make the most out of this newest toy! I would use this and the old paddle in parallel, at least in a ‘transitional time’, a second “storm paddle” is in plan, but only after I’m well – versed with this new one!

Initial testings prove the efficiency of the Greenland paddle, at normal cruising paddling pace, there’s no noticeable difference in speed, while it’s more lightweight and ‘handy’ to operate. And my boat proceeds with much more balance and hence, tracks better with this new ‘propeller’. I would trim the blades shorter (and also make it thinner at places), 210 cm is still quite long, I guess the final length would be somewhere between 200 ~ 205 cm, but only trials would tell the final, ideal fit.

I still need to test the new paddle more, to know if it could totally replace the wing paddle. In specific, I’m still worrying about its capability to provide enough force against strong head wind or other adversary conditions. Its efficiency under normal cruising situations is out of question.

My new paddle is light and firm, much more dependable compared to my previous one. And it is made of wood, looks better, not that ugly plastic outlook anymore. This one, when pulled hard through water, produces a mild vibrating sound, like a musical instrument, really interesting to hear! 😀

aving gained some know – hows from my first Greenland paddle, I proceed to making the second one. This is not a “storm paddle” as mentioned in the previous post, but rather just an auxiliary, backup one. It would be shorter (190 cm), and wider (10.5 cm), as my first one, though suitable for long range paddling, lacks the force needed to compete against really strong current and wind. I think it’s wiser to have a pair of paddles to compensate each other (and stop using the plastic one completely).

aving gained some know – hows from my first Greenland paddle, I proceed to making the second one. This is not a “storm paddle” as mentioned in the previous post, but rather just an auxiliary, backup one. It would be shorter (190 cm), and wider (10.5 cm), as my first one, though suitable for long range paddling, lacks the force needed to compete against really strong current and wind. I think it’s wiser to have a pair of paddles to compensate each other (and stop using the plastic one completely).

But first, I need to reshape my first paddle a bit, to make it even lighter, and turn the cross – sections from “rounded – rectangles” into real flat – ovals. The blades are still quite thick, especially at the edges, and they’re making quite some noises when entering the water. A good paddle should make as little sound as possible, so that the water birds wouldn’t fly away until you’d approached them within 4, 5 meters or so 😀. Well, those lovely water birds, an interesting story I would tell in another post.

5th image below: using a spokeshave to carve the edges (the rougher job is done with the machine planer already). I’d turned to love this tool, it removes wood easily and nicely. As I’m gaining more experiences with wood working, I feel more confident and rely more on the manual tools, as they allow me to do the finer jobs. 6th image: the pair of paddles, they’re just a little bit heavier than the plastic paddle, but feel like firm enough for hard uses though! Now ready for the glassing and painting tasks!

For true wild birds, it’s hard to approach them within 10 meters without signaling them on your presence. But for those “half – civilized” birds around my area 😀, they only fly away when I’m just 3, 4 meters apart. That implies some things on the city’s noise – pollution, I would suggest.

8th image: the blades’ tips get one layer of 6 – oz glassing on each side (which cover about 20 cm of blade length). Some light painting still needed to really finish them though, to protect the epoxy resin from UV! I’m eager to try out the two paddles in action in the next couples of day!

ontrary to my initial thinkings, the second Greenland paddle has proved to be the most satisfactory among mines. Despite its short length (190 cm), I’ve found it the best balance between length, blades’ width, weight and force. And that’s explainable, cause I have small arms and quite a short arm span, in body building, could be called a “bottom – heavy” type, my upper part is not too strongly built, unlike the lower part. And that has some advantages as well as some disadvantages in kayak paddling.

ontrary to my initial thinkings, the second Greenland paddle has proved to be the most satisfactory among mines. Despite its short length (190 cm), I’ve found it the best balance between length, blades’ width, weight and force. And that’s explainable, cause I have small arms and quite a short arm span, in body building, could be called a “bottom – heavy” type, my upper part is not too strongly built, unlike the lower part. And that has some advantages as well as some disadvantages in kayak paddling.

I could often balance the boat better in shaking situations, compared to the “top – heavy” type, but also, I usually find myself understrength when prolonged heavy paddling is required. Overall, I’m very pleased with my new pair of Greenland paddles, especially the second one. And that’s an attractive appearance, my boat with the two paddles, all of one same nice wooden style! 😀 On my paddling route, I usually meet and have some talks with the captain of a 2000 – ton dry – cargo vessel named UT Glory.

He proposed buying my kayak, and before I could make a polite refusal, he insisted: you know, price is not the problem!

😀. Well, at least someone who really want to have a nice little boat like her that much! It takes some moments choosing the right words to answer him, that I won’t gonna sell her, Serene – 1, my self – designed, self – built boat! And for sure, he wouldn’t be able to find anyone who could produce just a simple, hand – crafted kayak in Vietnam though, as far as I know.

Apart from some plastic, fiberglass kayaks used for “tourist attraction”, kayaking as a real hobby in Vietnam is virtually non – existent. That explains why the kayak – building, kayak market in VN is virtually zero, though designing, building one is not any big thing, I would say. Why so!?

Frankly speaking, I think VNese is busy drinking and talking bullshit! Seriously speaking, I think VNese has salt in their mouths, but no salt in their blood! Truly speaking, I won’t hope they would do anything besides trying to cheat someone for some dirty purposes! That’s all facts!

inal entry of the Serene – 1 series. There wouldn’t be any major updates, add – ons for the kayak since most everything is completed, and I need to shift my times and efforts into some higher – priority tasks. In a sense, an important milestone has been reached, the designing, building and equipping of my newest beloved kayak. A fascinating process at the beginning of which, I didn’t even think I could make it, and I didn’t know where it would lead to, a nice useful watercraft, or… a disaster!

inal entry of the Serene – 1 series. There wouldn’t be any major updates, add – ons for the kayak since most everything is completed, and I need to shift my times and efforts into some higher – priority tasks. In a sense, an important milestone has been reached, the designing, building and equipping of my newest beloved kayak. A fascinating process at the beginning of which, I didn’t even think I could make it, and I didn’t know where it would lead to, a nice useful watercraft, or… a disaster!

Serene – 1 is the best kayak of mine until now, outperforms all others in term of performance, lightweight and agile, pretty much fast, with some sacrifice in primary stability. Yet, it is not without some weak points that could be further improved, and that would be the concerns of my next boat project (still have no plan for that at the moment). I’d tried to get out with the best design, the best building as I could, learning lots of new things about a hull’s hydrostatics and hydrodynamics along the way.

But let me make a clear point about this, even the best cruising hull, the best equipments won’t improve your mileage by 15 ~ 20 percent, for a whole – day paddling. After all, it’s you, your horse – power output, your determination and physical endurance, which are the factors that could make a key difference. To be honest, sometimes, I have a strange self – satirising feeling that I’m quite like Popeye, the Sailor man cartoon character, especially before embarking on some longer journey! 😀

Where to go from here, now!? I have so many ideas on boat and boat – building, so much that I fear that I wouldn’t have enough time to carry them out all. But sometimes, I should be pleased with what I’m having, me, a nice little boat, and the immense water space to indulge myself in!

Time on water is the time well spent 😀, constant hard struggles, always keep a cautious eye on wave, wind and weather, be prepared for bad things, and reserve the other eye to enjoy the many different shades, different faces of the water. That’s truly serene for my mind then!

am in the progress of preparing for my next trips… so some more add – ons for my Serene – 1 kayak is a must. First is a deck mount compass. I’ve been long wanting a good compass with built – in LED lighting, for paddling at night, but that would require some kind of 12 or 24 Volt DC electric input, which my kayak doesn’t have at the moment. So I came up with a simpler compass available within my local market, and would just use a small flashlight to illuminate the compass instead.

am in the progress of preparing for my next trips… so some more add – ons for my Serene – 1 kayak is a must. First is a deck mount compass. I’ve been long wanting a good compass with built – in LED lighting, for paddling at night, but that would require some kind of 12 or 24 Volt DC electric input, which my kayak doesn’t have at the moment. So I came up with a simpler compass available within my local market, and would just use a small flashlight to illuminate the compass instead.

Next is building a “cup” to hold the compass, which would then be mounted, recessively, onto the front deck of my kayak. I use a thin strip of oak veneer to build the cup, turn it two rounds around the compass (with Titebond – 2 glue in between), then add the plywood top and bottom parts. The whole thing would be reinforced with some fillet at the jointing edges, then a layer of glass. It requires some handiness to build the “compass cup”, as its size is quite small and my hands are big and clumsy! 😀

I hate having to punch a hole into my kayak, but it need to be done to fit the compass holder in place. That’s quite straightforward the job, cutting a round hole some distance in front of the cockpit, just before the bungee lines, gluing the compass holder with some epoxy, then some little painting outside. Et voila, here it is, the compass in its working position, it looks so great! And as they usually say: May your anchor be tight, your cork be loose, your rum be spiced, and your compass be true!

😀

It’s not immediately obvious for me to see why this compass dial (the compass rose) is reversed, looking from above, it’s flipped so that the North becomes South, East becomes West. It took me some minutes to understand the rationale behind that “weird” fact 😀.

Cause in most cases, the boat handler would be sitting, looking forward, so the indicated direction facing him is actually the heading (bearing) of the boat’ stern (not the boat’s bow). Flipping the compass rose would give a correct and convenient reading for the sailor.

ext is the paddle float used to assist kayak reentry. Often we’ve seen experienced kayakers performing some kinds of rolling, but for most people, that could only be done with an empty boat. When it’s fully loaded for long journey, it’s almost impossible to roll that heavy hull. The most practical way is, of course, just climb in via the aft deck. My paddle float is just a supermarket plastic bag, I hate needle and thread things, but some little tailoring work would be needed to turn a bag into the float.

ext is the paddle float used to assist kayak reentry. Often we’ve seen experienced kayakers performing some kinds of rolling, but for most people, that could only be done with an empty boat. When it’s fully loaded for long journey, it’s almost impossible to roll that heavy hull. The most practical way is, of course, just climb in via the aft deck. My paddle float is just a supermarket plastic bag, I hate needle and thread things, but some little tailoring work would be needed to turn a bag into the float.

It’s just a quick job stuffing the bag with Polyurethane foam. The float is made such that it could be quickly attached (and detached) to one end of the paddle to assist boarding the kayak from water. One of the most important equipments for a cruising kayak is… a radar reflector. Here I should emphasize its importance a hundreds times, as with experiences gained in my previous paddling trips, your kayak is just so small compared to those huge freighters, looks like just a peanut shell in the sea.

And without a radar reflector, I’m sure that you would probably not be seen from above those high ship bridges. And as a big ship is approaching you, the situation is really critical: to be seen or to be sunk. Having a reflector would boost your boat’s radar signature, and it works best in combination with a marine handheld radio. My radar reflector would have a tubular form, erected on the aft deck, and it functions also as a signal light mast, with a red – blinking light attached to the top.

The elements of the radar reflector are made from thin steel plates, welded together to create some prism shapes. 8 pieces like that would be put inside a PVC tube (the signal light mast), which create an object with a radar – cross – section of about 1.4 m2 (estimated).

The ugly part about a home – made radar reflector is that you have no way to tell if this equipment works well, how big your boat would appear on those big freighters’ radar screens. But it’s better to have something, hoping that it should work, rather than having nothing at all.

mages below, 1st: the parts of the signal – light mast, 2nd: the signal – light mast (with the tubular radar reflector inside) in its erected position, 3rd: retracted position on the aft deck, 4th: the red – blinking signal light. I would install a small strap near the mast head to mount the GoPro camera. For the mast base joint on the deck, I was searching for a Rosette clamp (Vietnamese: ngàm hoa thị), so that the mast could be rotated around, but can’t find one, so I use this instead.

mages below, 1st: the parts of the signal – light mast, 2nd: the signal – light mast (with the tubular radar reflector inside) in its erected position, 3rd: retracted position on the aft deck, 4th: the red – blinking signal light. I would install a small strap near the mast head to mount the GoPro camera. For the mast base joint on the deck, I was searching for a Rosette clamp (Vietnamese: ngàm hoa thị), so that the mast could be rotated around, but can’t find one, so I use this instead.

Last image below: the IC-M25 VHF radio used in conjunction with the radar reflector to avoid collision with big ships, it’s better to have a channel of communication with vessels around you and a way to ask for help when needed. The radio floats on water, it has about 11 hours of battery, and best of all, could be charged via a USB cable (that means it could be charged by a smart phone power bank). There’s another very important use of the radio: to listen to the broadcasted weather news.

I also hoist a tiny Vietnamese flag on the signal mast, not because I like hoisting color, but it’s good to gain some sympathy from the Vietnamese border guard or maritime police along my paddling way 😀. That’s about all I could do for my Serene – 1 kayak, preparing it for my next trip (that gonna be a long trip). Of course I have lots of other ideas on kayak building and equipments, but that would be reserved for my next boat, Serene – 2, which I’m gonna work on its design soon in the upcoming time.

The other day, I took Serene – 1 out to test paddling at full load, 16 bottle of water containing 1.5 liter each, so about 24 kg in total. Though the boat is a bit heavier to paddle, it becomes very stable at its nominal (designed) load. That made me feel very pleased and confident!

The boat could probably take a bit more, about 25 ~ 30 kg of load I guess. Since I designed it as a very lightweight sea kayak, I’m now having some headaches in loading it with appropriate food, drink and gears for my up coming trip (would tell about that in my next posts) 😀.

PHOTO ALBUMS

For more details, see a complete photo building log in the albums below: